VCs boost investment in Black- and Latinx-owned fintechs

The spark for a business idea often comes from the founder’s personal experience or a plan to serve a specific market. That can create unfair odds when the financial gatekeepers don’t have the background to relate.

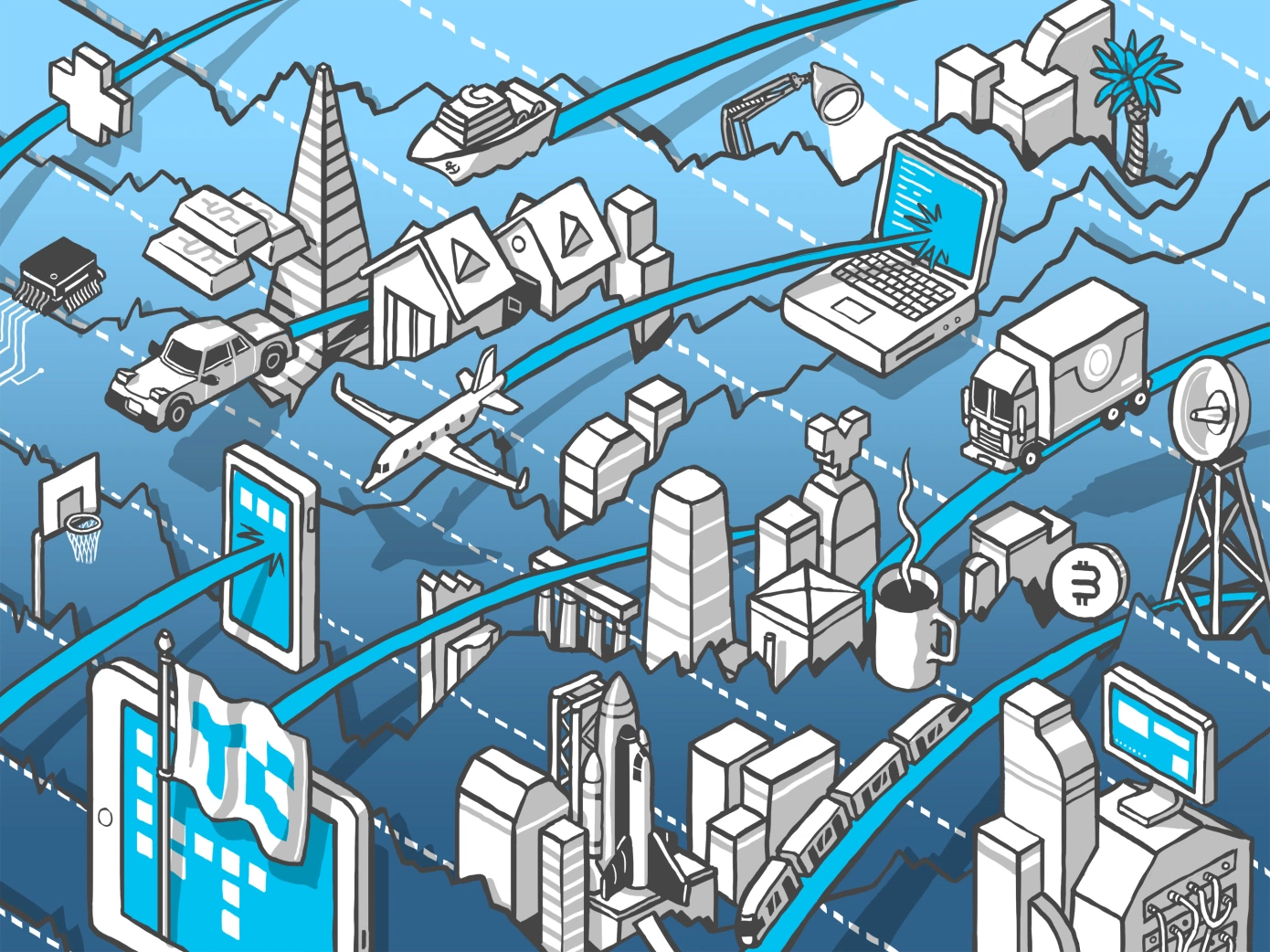

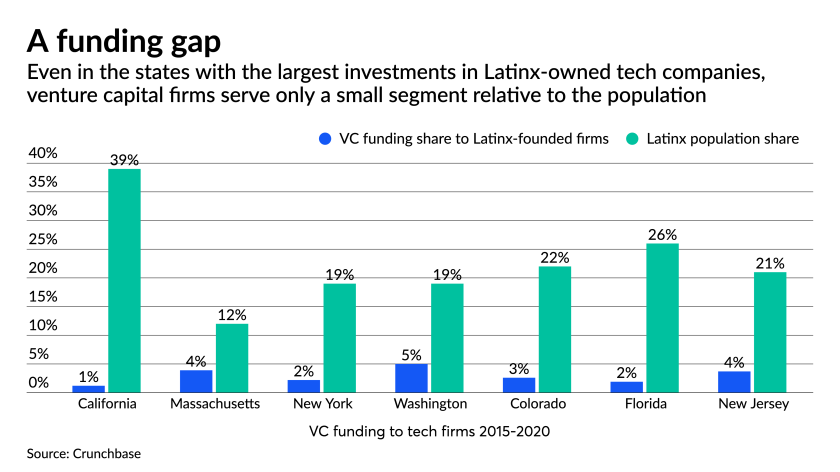

Technology investments are not distributed in a manner anywhere consistent with the United States’ racial and ethnic composition, and as a result there’s a risk that financial innovations can be missed and new markets overlooked. Across all technology categories in the U.S., the venture funding gap for Black or Latinx-founded startups is staggering. Since 2015, about $15 billion has been raised by Black- or Latinx-founded technology startups, which is 2.4% of the total venture capital raised during that time, according to Crunchbase.

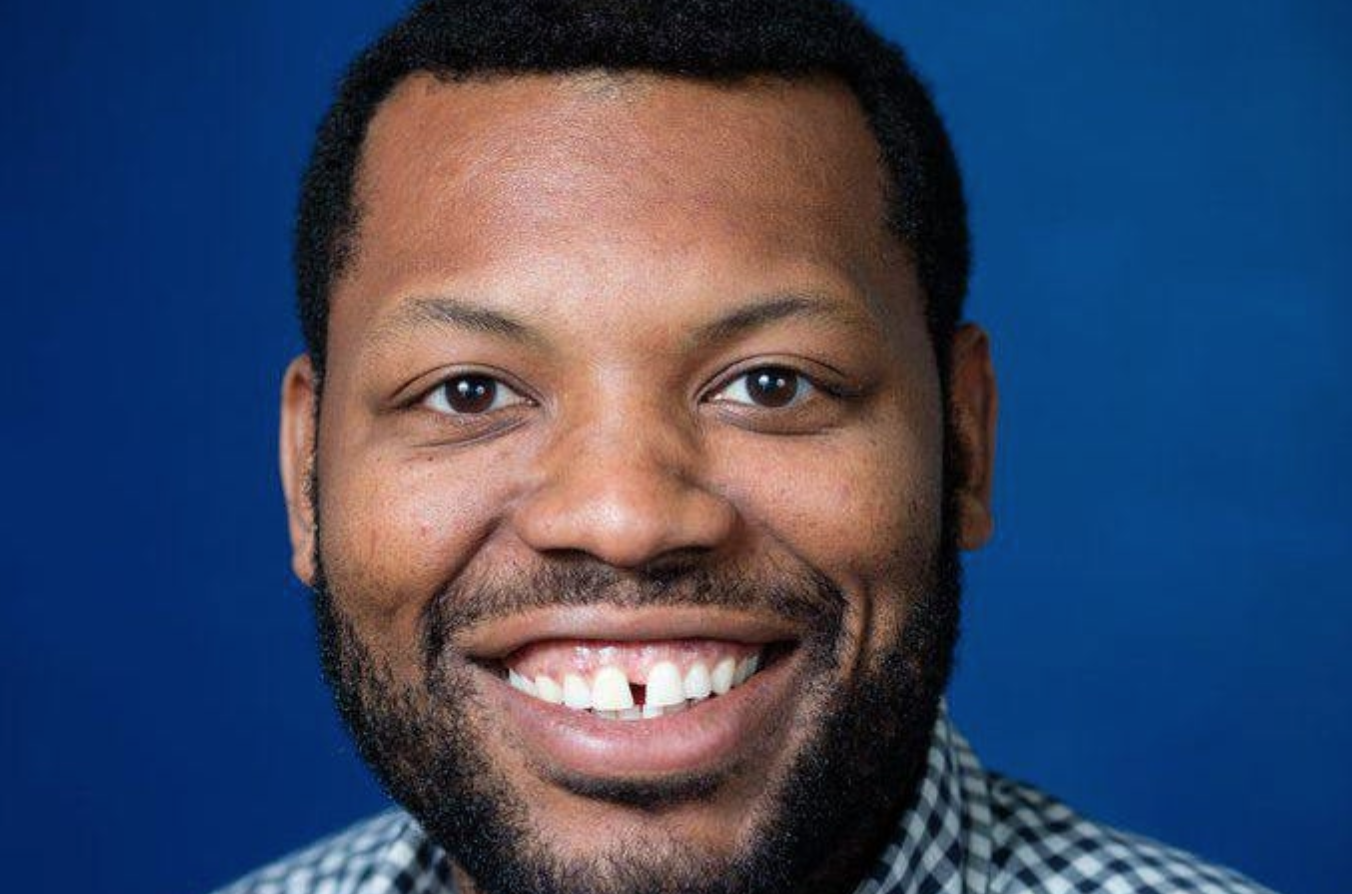

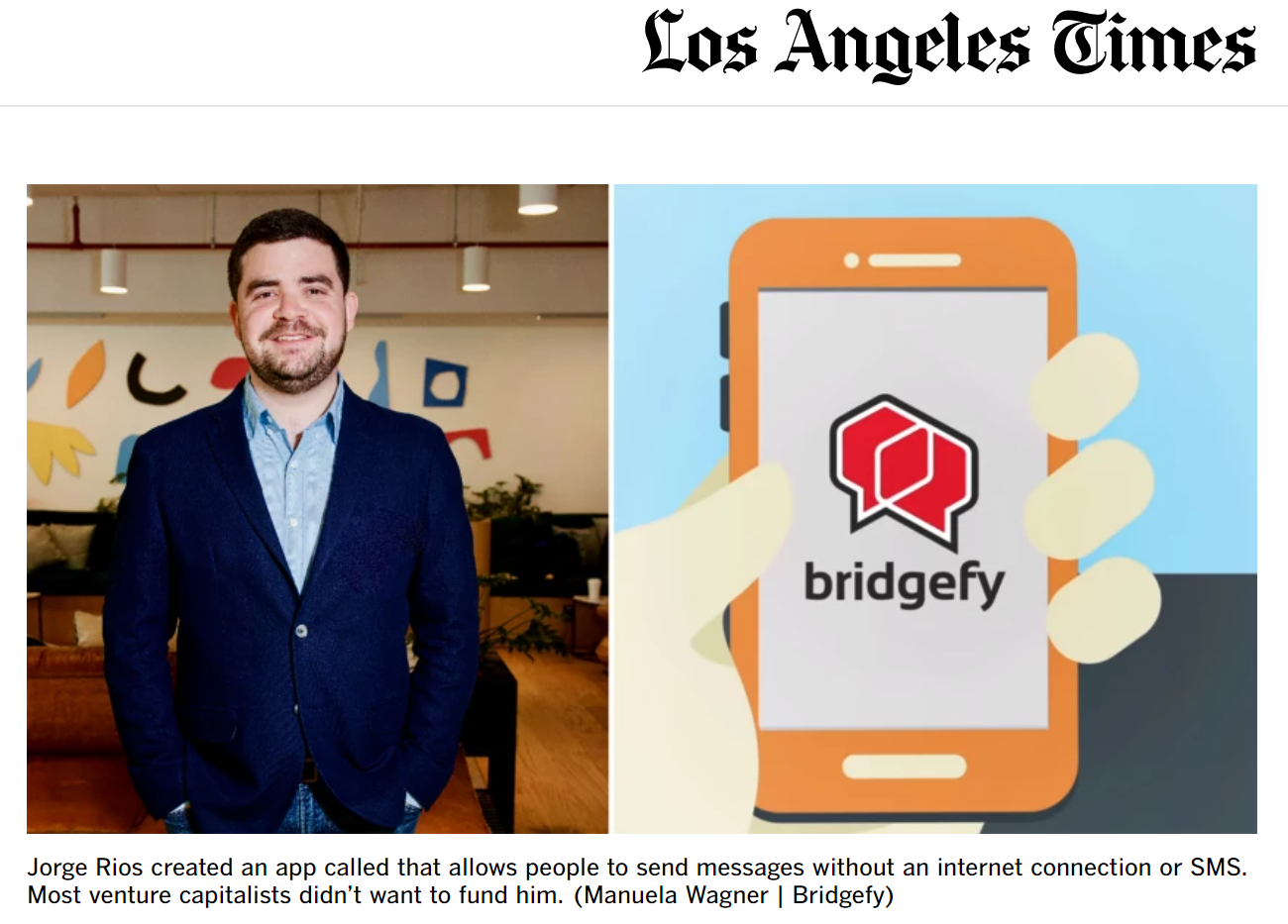

“We are focused on serving the Latinx community, and it has taken a while for the VC community to really understand the customer pain points we are addressing,” said Sam Ulloa, CEO and co-founder of Listo, a San Jose, California-based payment and financial services company that recently received funding from Mendoza Ventures, a Latinx-owned VC. “The stats clearly show that it is more difficult for Black- and Latinx-founded fintechs to obtain VC funding. There are multiple reasons, one of which is simply a lack of access to the right networks; the second is that there aren’t enough Black and Latinx VCs.”

Mendoza Ventures in Boston is one of the firms working to address a funding gap for technology startups in underserved markets with a specific focus on pre-seed investments, or spotting an innovative concept early on. Adrian Mendoza co-founded the organization, one of the first Latinx-owned VC funds on the East Coast, with his wife Senofer in 2015.

“There’s a tremendous opportunity for fintech to democratize access to financial products,” said Mendoza, general partner of the firm.

Seventy-five percent of the firm’s investments go to companies that are led by immigrants, people of color or women, mostly in AI and fintech. “The tech has to be there, but a diverse team can create an impact and reach and improve financial conditions for a new market,” Mendoza said.

Listo’s model, including its bilingual website, is designed for the needs of its target audience. It uses an internal algorithm based on prior transactions to create risk profiles for people who often do not have credit scores. Listo then offers digital payment products, microloans and insurance to businesses and consumers that are largely cash-reliant and can have liquidity challenges.

“It is natural for VC investors to invest in things they can relate to,” Ulloa said. “That’s another reason why diversity is so crucial.”

Root cause

The VC funding gap for fintechs and payment companies starts with a cultural imbalance in the investment industry. Venture capital is a field that is numerically dominated by white men on both sides — investing and receiving — said Katherine Klein, vice dean of the social impact initiative at the University of Pennsylvania.

“VC is a highly relational, predictive business, in which investors often make decisions and predictions about an early-stage company’s future success based in large part on relationships and ‘gut instinct,’ ” Klein said. “Relationships matter, because only a very small set of early-stage companies and their founding teams can secure the attention of VCs.”

That relationship gap can be traced directly to the ownership of investment companies.

According to the Knight Foundation, “substantially diverse-owned” and “majority diverse-owned” firms manage 1.3% of assets under management in mutual funds, hedge funds, private equity and real estate in the U.S. (Majority diverse-owned firms have 50% or more owners who are nonwhite male, while substantially diverse-owned firms have 25 to 49% nonwhite male owners.)

“It’s not surprising VCs pay more attention to founders they meet through their personal networks,” Klein said. “But, because our social networks tend to be homogeneous, VCs are exposed to and are most likely to invest in people who are like them.”

The gap in VC ownership does not correlate to performance, according to Knight, which found no difference between the performance of diverse-owned and nondiverse firms. Diverse-owned firms are also more likely to invest in diverse companies, according to a Fairview Capital study.

VC firms can change their recruitment practices to bridge the representation gap, according to Klein.

“It’s really important for VCs and other decision makers to think long and hard about the indicators they use to screen candidates,” Klein said. “How valid are these indicators? By relying on these indicators, who are they excluding? And, how might they evaluate and predict quality in a way that is more valid but less restrictive?”

‘Talent is ubiquitous’

Fairview found some progress, noting 69% of women- and minority-owned private equity firms in the U.S. market in 2019 were pursuing venture capital investments, up from 62% in 2018. The trend is attributable to an acceleration of new VC firms focused on early-stage investments, which are key to a company getting off the ground.

“Often startups led by diverse founders have a hard time even getting to a Series A round,” said Trish Mosconi, executive vice president, chief strategy officer at Synchrony, which recently set aside $15 million for female and minority-backed VCs. “To start narrowing the funding gap, diverse founders need access to capital at an earlier stage so their companies have a better chance to grow.”

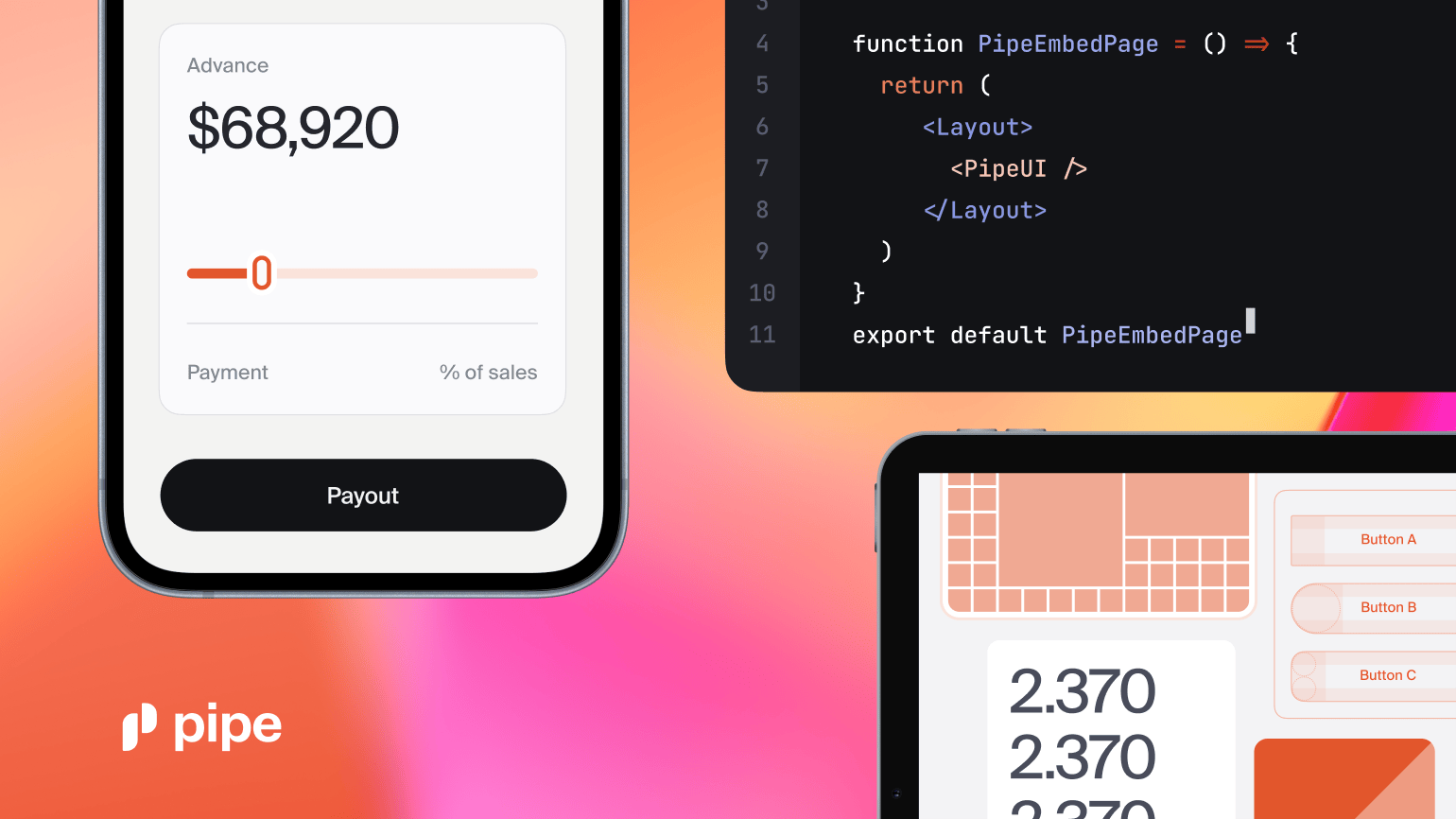

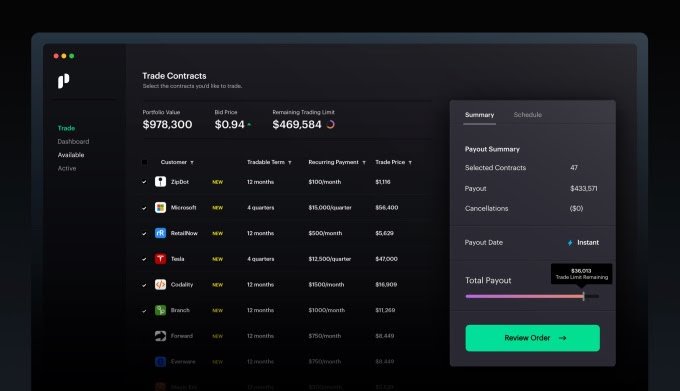

Mendoza’s investment strategy often leads it to firms that develop and sell payment and banking products based on nontraditional metrics. Mendoza portfolio firm Finch offers a combination of checking and an investment account with a link to an exchange traded fund. There’s also a debit card that tracks payments and routes transactions to investments and wealth management services.

The Boston-based company’s product is designed to address wealth inequality, another dangerous gap. The median wealth for U.S. white households grew about $54,000 over the past decade and a half, while the median wealth for U.S. Black households stayed stagnant, according to McKinsey, which estimates the perpetuation of these trends will cost the U.S. economy as much as $1.5 trillion, or 6% of the GDP, by 2028.

The pandemic’s impact was disproportionate, creating a greater economic challenge for Black and Latinx-owned businesses, which have more difficulty accessing credit and greater liquidity issues than white-owned small businesses, according to McKinsey.

“One of the things that is financially hurting minorities and millennials is they are sitting on cash … they are losing out on net worth,” Mendoza said. “And that cash can go into wealth generation.”

Established financial firms are starting to address the VC gap. In addition to Synchrony’s recent investment, PayPal in late May announced it would invest an additional $50 million in 11 Black and Latinx-led early-stage VCs, following an earlier $50 million in October 2020.

In an email, a PayPal spokesperson said PayPal Ventures has made about 40 investments in the past four years in “promising startups, mostly series B and larger funding rounds in fintech and e-commerce space.” PayPal realized the majority of Black and Latinx founders often struggle to raise early-stage funding, leading to the $100 million commitment, the spokesperson said.

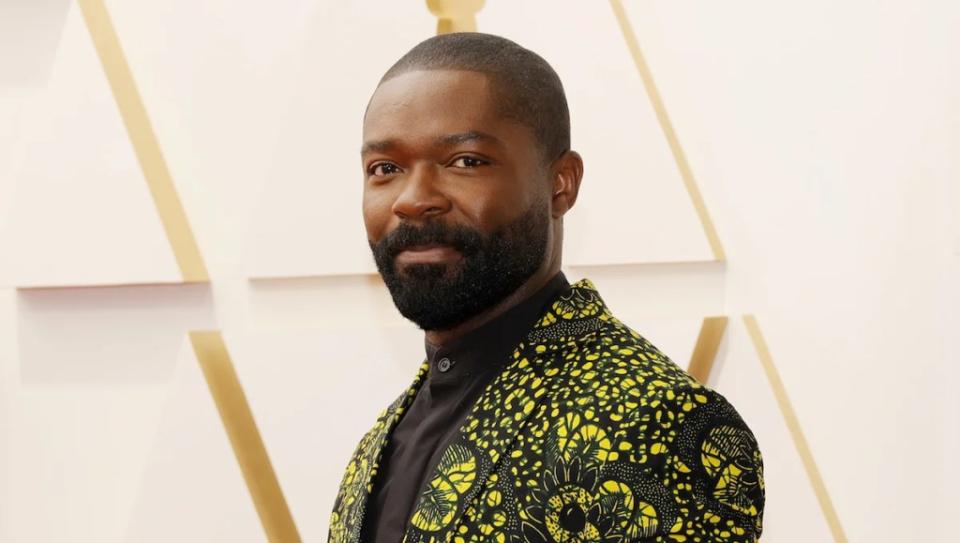

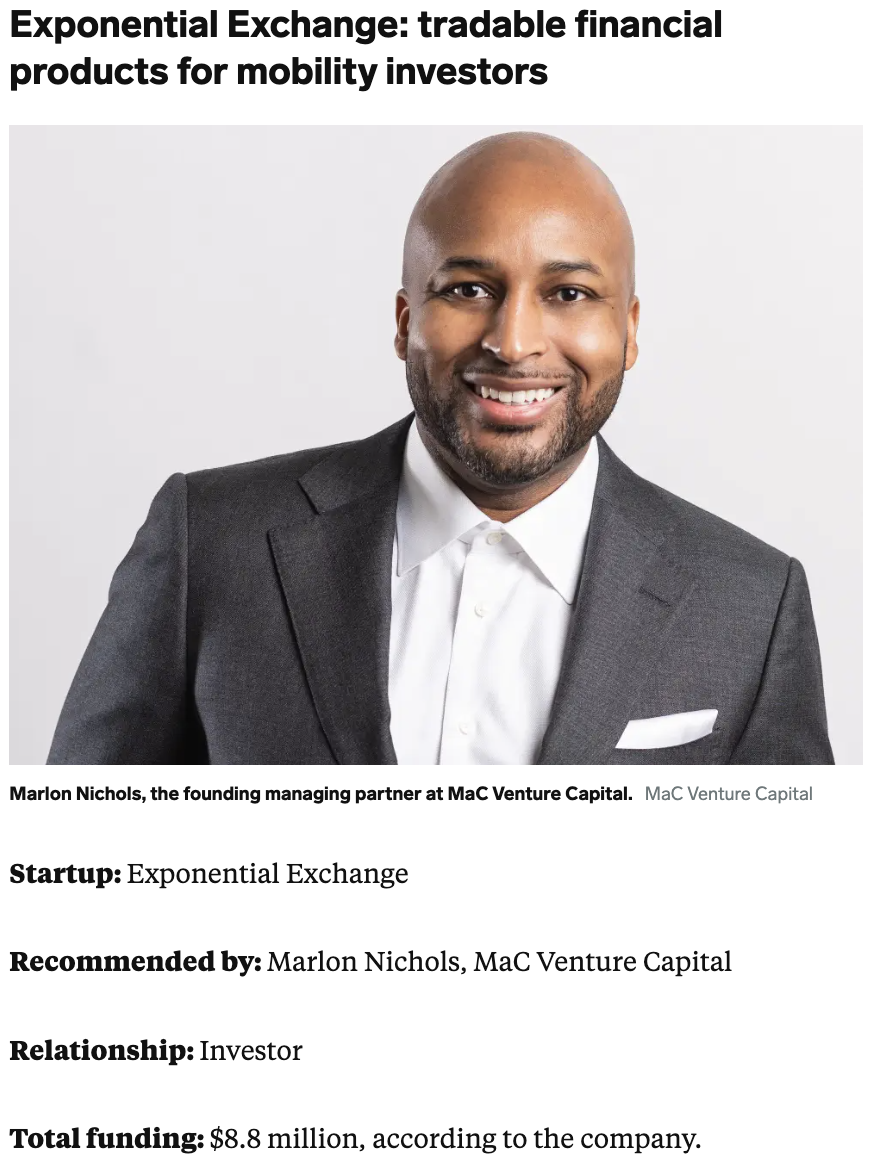

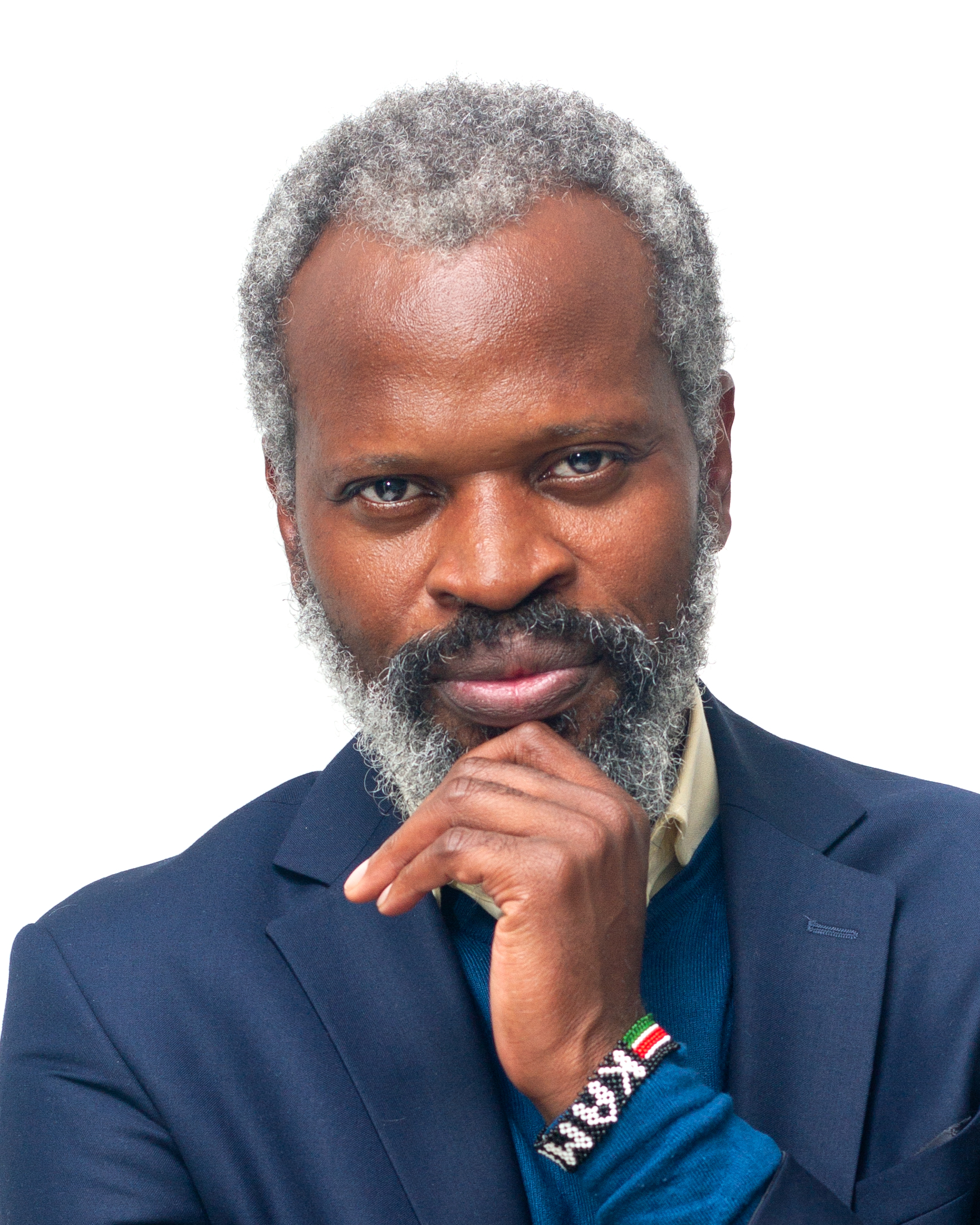

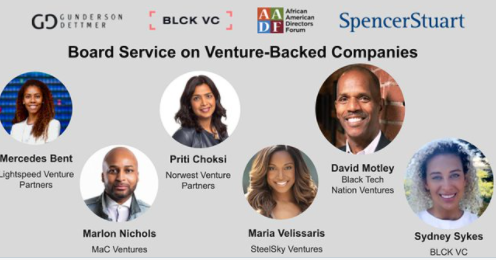

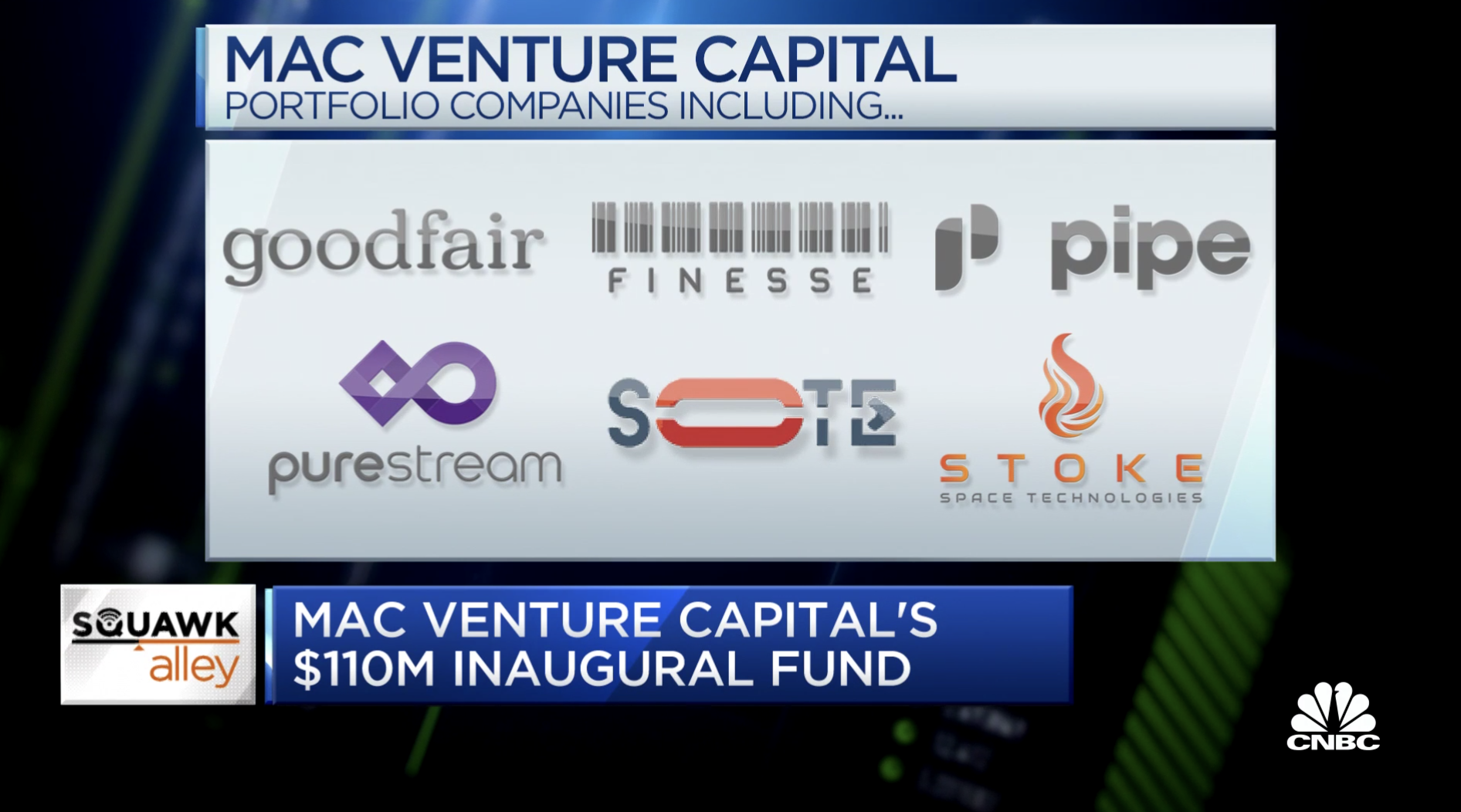

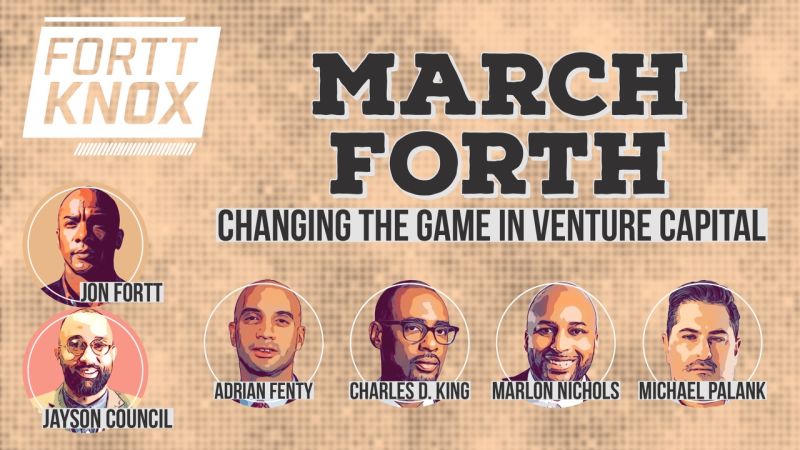

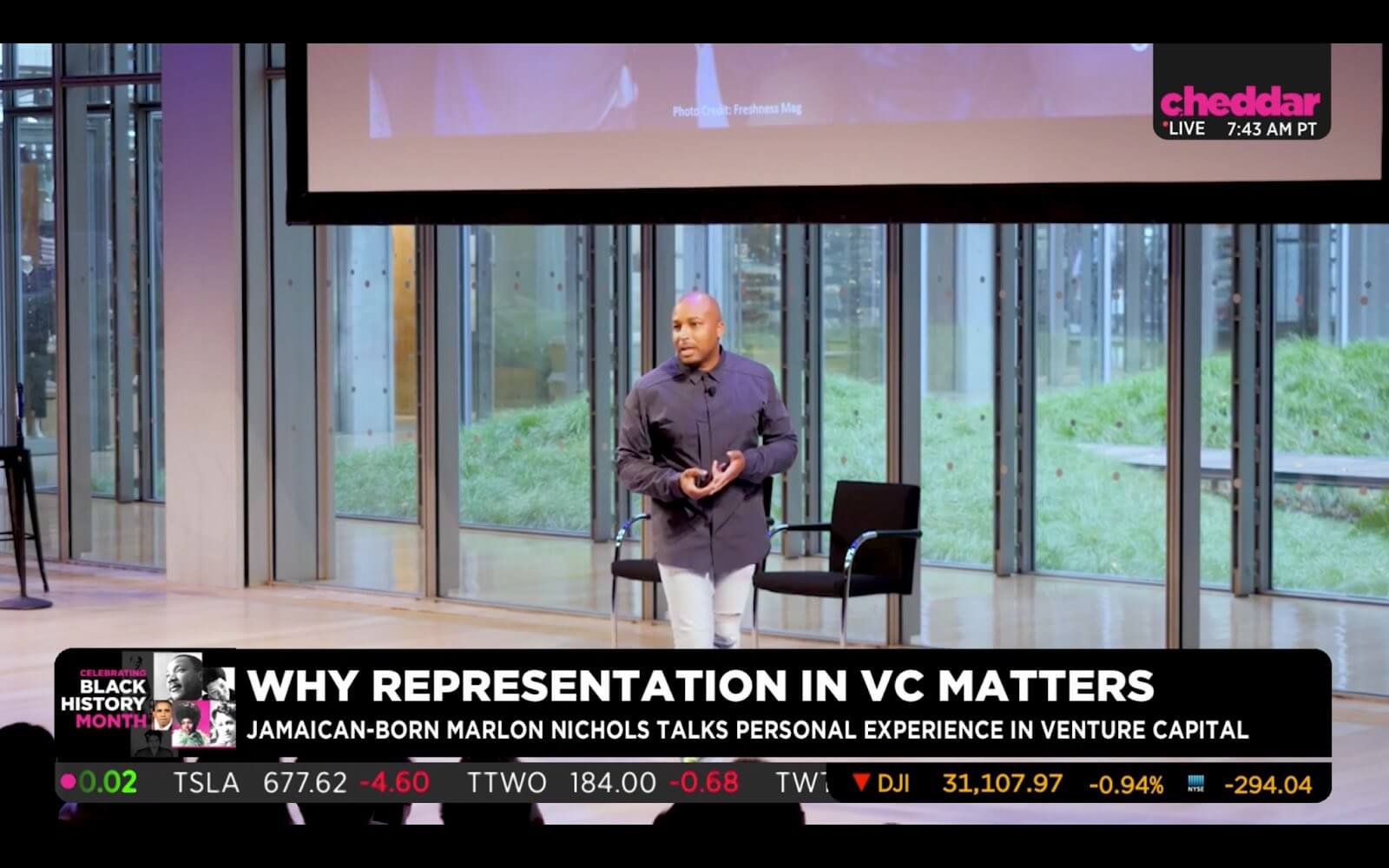

“Talent is ubiquitous, but access to capital is not. This is evident in the lackluster percent of venture dollars that make their way from VCs to Black and Latinx founders. To solve this problem, like any other, we must attack it at the root,” said Marlon Nichols, managing general partner and cofounder of MaC Venture Capital, a Los Angeles-based VC partly backed by PayPal.

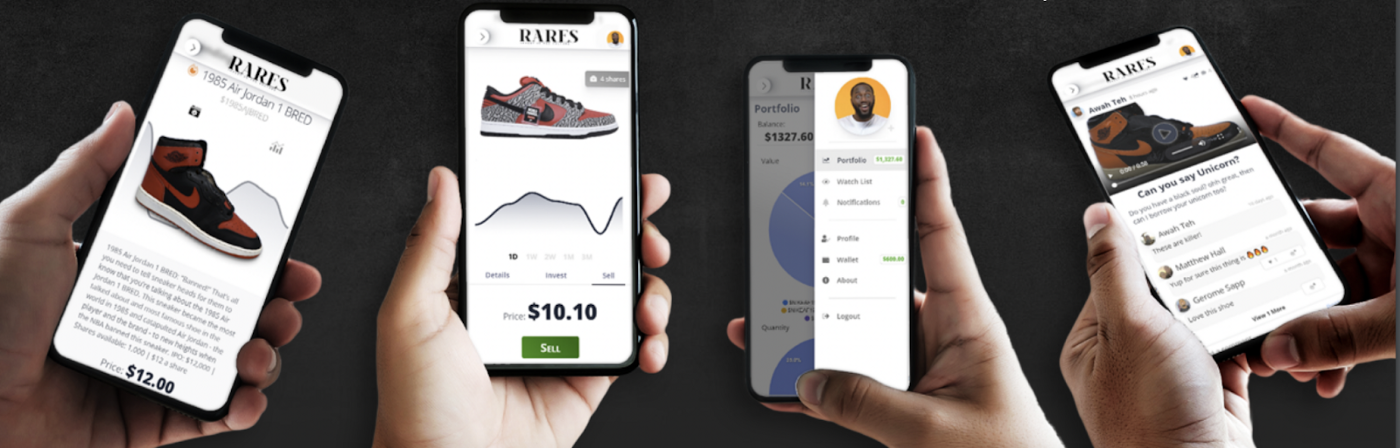

MaC Venture’s current portfolio is invested in 76% Black, Latinx and female founders, with recent investments including StoreCash, a San Jose, California-based payment company that allows users without bank accounts to request, receive and use funds via their smartphones. There’s also a StoreCash payment card.

“The larger VC industry needs to focus more on entrepreneurs at the early stage and invest in those who are solving the problems that would benefit the majority of our society,” Nichols said.

Mastercard this month launched a new track for its Start Path program for new technology companies, focusing on startups with Black, Indigenous, people of color and/or women founders. The program includes partnership readiness training, coaching, introduction to investors and in some cases grants.

The VC funding gap is particularly acute for Black women founders, which have received 0.27% of VC funding during the past two years, said Michael Froman, vice chair and president of strategic growth for Mastercard, who stressed mentorship and guidance as part of the solution.

“A startup’s ability to scale increases exponentially when larger companies with trusted relationships can make introductions to its partners, but also offer the startup’s services as part of a proposed solution to customers,” Froman said.

Another VC, the two-year-old Chicago-based Chingona Ventures, has focused its investments on payment technology that addresses changes in business practices and in consumers’ shopping habits, with a focus on finding diverse developers and founding teams.

Chingona’s portfolio includes Finix, a San Francisco-based company that offers a payment facilitation platform as a service that handles merchant onboarding, a payment gateway, tokenization, reporting and reconciliation that’s designed for a range of businesses that may not have digitized their payments in the past.

“The restaurant space got hit the hardest. In many cases the restaurants weren’t prepared to track payments digitally and had to adjust quickly to that trend,” said Samara Hernandez, a founding partner at Chingona. “And that will continue going forward.”

Another Chingona portfolio company, the Los Angeles-based Reel, allows users to create an account to gradually save toward purchases, with a calculator that displays how long it will take to afford the item based on a current rate of spending.

It’s a buy now/pay later model in reverse, based on saving instead of debt.

“There are a lot of consumers that don’t want debt and don’t want to put purchases on a credit card,” said Hernandez, who has worked in venture capital for more than seven years and has also worked at Goldman Sachs.

An additional Chingona portfolio company, Suma Wealth in Los Angeles, offers consumer wealth management products to the Latinx community, selling a mix of payment cards, investments, savings and other financial products. There are also financial education products for young people.

“They serve an educated market with a high income that many companies don’t know how to target,” Hernandez said.

This article was written by John Adams for American Banker.