This U.S. city just voted to decarbonize every single building

The city of about 30,000 people consists of some 6,000 homes and buildings. Decarbonization would involve looking at everything from how a building is heated to what appliances it uses, with the aim of moving away from the consumption of fossil fuels such as oil and natural gas.

“It’s a project for the whole city, not just municipal buildings,” said Aguirre-Torres.

Buildings account for nearly 40 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Ithaca’s initiative is projected to cut about that much from the city’s overall carbon footprint — saving approximately 160,000 tons of carbon dioxide. That’s the equivalent of the emissions from about 35,000 cars driven for a year.

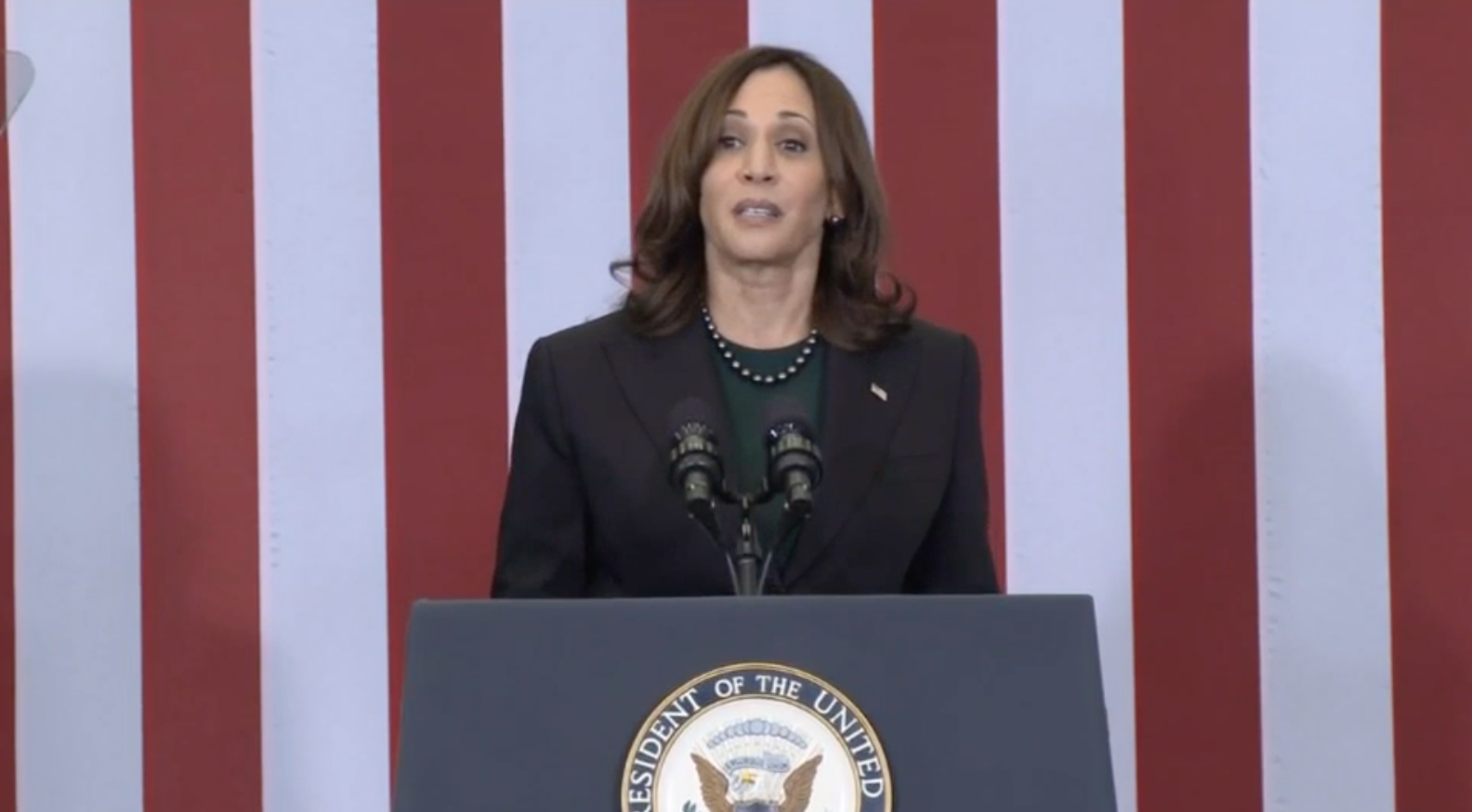

“There isn’t a single day where I don’t worry about what climate change means for our kids,” said Donnel Baird, a founder of BlocPower, a Brooklyn-based company focused on “greening” aging buildings. Ithaca chose BlocPower to manage its initiative. Baird said the vote has marked a milestone.

Ithaca’s common council voted unanimously in favor of this latest move, which is part of the broader Green New Deal that the city approved in 2019. That measure calls for the city government to meet all of its electricity needs with renewable energy by 2025, as well as reduce its vehicle emissions by half. Most ambitiously, though, it set a goal of being a carbon-neutral city by the end of the decade.

Aguirre-Torres said the city lost precious time to the coronavirus pandemic, which effectively shrank the timeline from 10 years to eight. “I had to come up with a very aggressive strategy,” he said.

The decarbonization effort is officially called the Efficiency Retrofit and Thermal Load Electrification Program. Building improvements could range from swapping natural gas and propane cooking stoves with electric induction cooktops to installing solar panels.

Timur Dogan, a professor at Cornell University, which is located in Ithaca and is consulting with the city on the project, said researchers are working on modeling to help inform what buildings to tackle first. But the program is broadly slated to unfold in two phases — the first covering 1,600 buildings and then another 4,400.

The goal, Aguirre-Torres said, is to reach full building decarbonization by 2030 and have the first phase done in the next three years. Baird said that may take closer to four or five years but is certainly achievable. He pointed to BlocPower’s work in Brooklyn as proof, saying that the company retrofitted more than 1,000 apartments there in under two years.

“We have the track record,” said Baird.

Dogan said the timeline is “ambitious” but is technically feasible. “The technology we’re talking about implementing here is already off the shelf and readily available,” he said. “It’s a matter of political will and financial means to make this happen.”

The city, whose total budget is only about $80 million, is turning to the private sector to fund its building decarbonization effort. The idea, said Aguirre-Torres, is to fund the program using private equity and then help reduce the costs of the capital via state and federal incentives, as well as manufacturer rebates. The city would also establish a fund that, bolstered by philanthropic donations, would further help lower the cost of the program, especially for low-income households.

“It would be equivalent to having zero percent interest,” he said, adding that the city has already raised the $100 million it needs for Phase 1. If that progresses well, it would then start looking for the additional $450 million necessary to cover the projected costs of Phase 2, he said.

“I don’t look at this as an environmental issue,” said Aguirre-Torres. “It’s an economic issue that can be solved with creative financing schemes.”

Ithaca is far from the only place championing climate mitigation and adaptation plans. Facing rising temperatures, Miami has appointed a chief heat officer. In New York City, the mayor has an office dedicated to climate resiliency. In northwest Canada, the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation declared a climate emergency and is also targeting net-zero by 2030.

Aside from buildings, Aguirre-Torres said transportation and the electric grid are Ithaca’s other significant sources of emissions. And, from aiming to double rooftop solar to developing a program to get used electric vehicles in the hands of low-income people, his plans are no less ambitious.

“I believe that all of this is possible,” he said. “We can be a replicable model for a lot of places.”