Starting a business — and raising money to fund it — is no easy feat.

Beryl Stafford, a food entrepreneur in Colorado, has raised more than $18 million for her baked-goods business Bobo’s. Lindsay Holden, a tech entrepreneur in San Francisco, has brought in $17 million in funding as a cofounder and the CEO of Long Game.

The two shared how they did it and their tips for other burgeoning founders.

Leverage a local reputation and strong growth

Stafford launched Bobo’s in 2003 and bootstrapped the company herself, having taken on credit-card debt, a second mortgage on her home, and some small bank loans.

She hadn’t known anything about food distribution or sales at the onset, she said, but created a successful business thanks to her connections to trade shows and her local community. In 2020, Bobo’s revenue hit $33.5 million, in large part because of its pivot to e-commerce.

Stafford told Insider she was petrified to pitch to investors, as she couldn’t just stand behind a table and feed people her product like at a trade show.

“I couldn’t hide in my own vacuum anymore, but I kept at it,” she said. She went to every type of food distributor, gluten-free consumer, and coffee trade show she could to find like-minded investors and highlighted Bobo’s market fit and “strong velocity on the grocery shelf,” she said.

“Network like crazy, and you will meet one or two investors that believe in you,” Stafford said.

Since she’d built a reputation in Boulder, she also aimed to keep investment close to home and partner with local firms. Bobo’s first fundraise was a $8 million Series A in 2017 led by Boulder Food Group, followed by a $4 million Series B in 2019 led by Boulder Investment Group Reprise, and the Boulder investment firm Range Light LLC.

“The standard advice in raising money is to do it before you need it. Don’t wait until you’re desperate,” Stafford said.

Use tough questions to refine your pitch

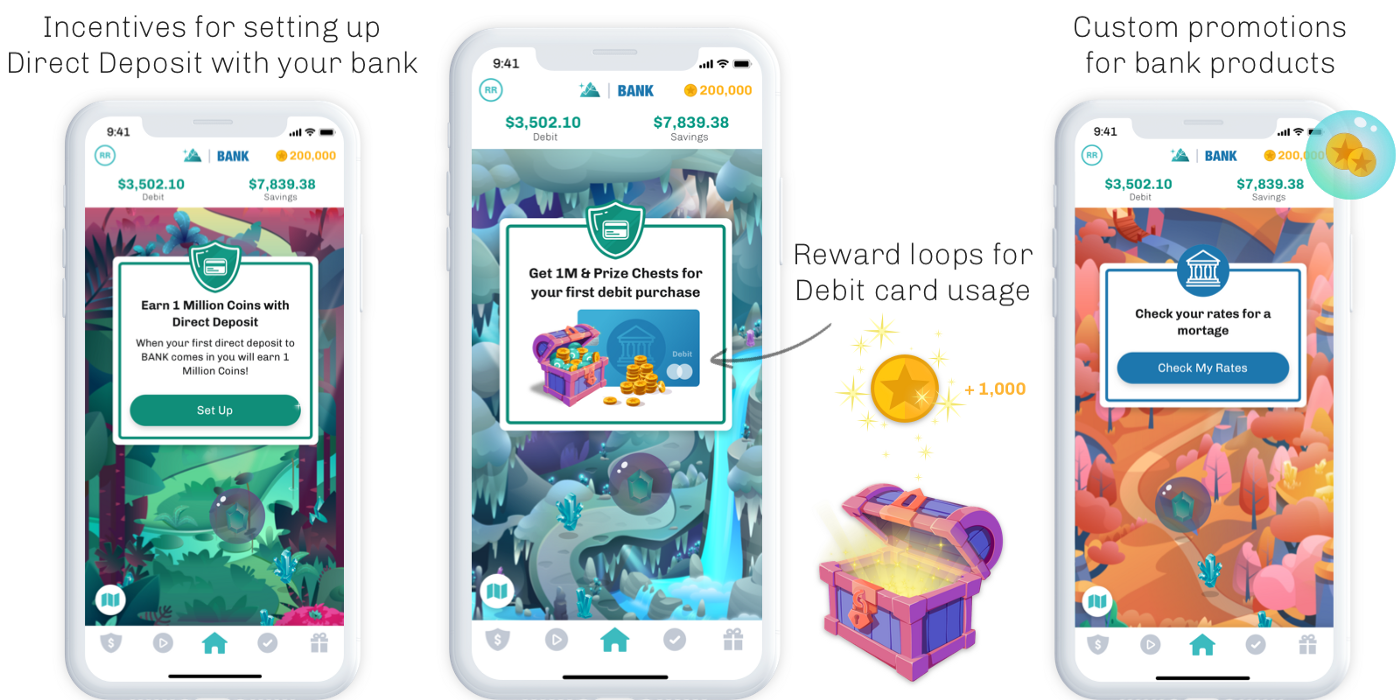

Holden, whose financial-planning app uses prize-linked savings and rewards to help users save money, told Insider she had pitched investors hundreds of times. Before Long Game, she cofounded an auction startup and worked in venture capital.

“Every fundraise, you go in thinking the company could die at this moment. It’s hard, scary, and a lot of pressure,” Holden said.

But, she added, it forces you to figure out what’s working and what’s not when pressed with hard questions.

“You may realize you need to explain some things with additional data or illustrative stories. It’s an iterative process on how to communicate about the company,” Holden said, adding: “You’ll start to see patterns in the questions asked, so you’ll then make sure to cover those when you pitch again.”

If a venture capitalist questions the value proposition of a business, for example, then you may need to explain customer motivations or problems in more detail.

“You may also need to break down your various customer-acquisition channels, such as paid search or marketing, and provide data that shows you can scale,” Holden said.

Long Game’s investors include Vestigo Ventures, Franklin Templeton, Thrive Capital, and Collaborative Fund. The company raised a bridge-financing round as it changed its business model, which last year moved from business-to-consumer to business-to-business.

Stay confident, Holden said, but be comfortable admitting what you don’t know.

“People aren’t really trying to stump you — they are trying to understand your business,” she said, adding that there had “been times I had to get back to them with an answer or a specific business-case model.”

“Always seek input from people who understand your industry and how investors think, and remember that building a company is more difficult than fundraising,” she said.

This article was written by Kathryn Kyte for Business Insider.