No Bank, No Problem: StoreCash and A New Way to Pay

No Way to Pay

Debit and credit cards have become so ubiquitous in society that we almost don’t even notice when we pull them out to pay for everyday items like groceries, gas, a haircut or a meal. We’ve come so far, that sometimes all you need to do is press a single button on your smartphone to make a payment (or no button at all as with Uber and Lyft). And if we need cash, there are more ATMs across the country than coffee shops. Payment options are always close at hand.

But unfortunately, this is not true for everyone. If you’ve ever realized you’ve forgotten your wallet midway through a trip to the grocery store and wondered how exactly you’re going to pay for all the items in your cart, you can start to get a sense of how millions of Americans with no or limited access to banking accounts feel on a daily basis. Paying for everyday essential items can be a stress-inducing, complicated task. A common cause of these payment challenges is the lack of access to traditional bank accounts and services.

The terms ‘unbanked’ and ‘underbanked’ although simple, allude to a very complicated and major issue in financial inclusion. Unbanked refers to a person or household with no checking or savings account. These individuals do not have any form or relationship with traditional banks and financial institutions. Underbanked means that an individual or household has a bank account but goes outside of the bank for financial services such as money orders, check cashing, payday loans and more. They have access to a bank but cannot or do not rely on that relationship to fulfill all of their financial service needs. To put it in numbers, 8.4 million households were unbanked in 2017 equating to 14.1 million adults who don’t have a checking or savings account. Another 24.2 million households that were considered underbanked, or approximately 48.9 million adults. That’s almost 65 million adults, representing 25% of US households who don’t enjoy the benefits of financial inclusion. And what’s worse is the fact that the majority of the unbanked and underbanked are communities of immigrants and people of color who have low income as a commonality and lack the minimum balance to open checking and savings accounts. Low income, plus few options to pay for goods and services, equals hardships these communities do not need or deserve.

Understanding the Unbanked Problem

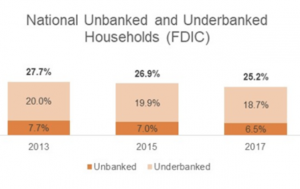

Why would an individual be unbanked or underbanked? It’s often not a choice. A 2017 FDIC National Survey showed that over half of unbanked households cited “do not have enough money to keep in an account” as a reason for not having an account. 30% of households also listed distrust of banks as a reason for not having an account. Despite this, the rate of unbanked and underbanked households is on a downward trend, albeit slow.

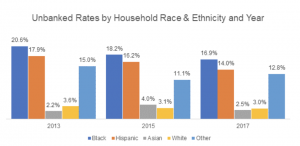

Unsurprisingly, however, the lack of financial inclusion is not equal among different demographics. The survey found that “unbanked and underbanked rates were higher among lower-income households, less-educated households, younger households, Black and Hispanic households, working-age disabled households, and households with volatile income.” While the national unbanked rate is 6.5%, it is 16.9% among Black households and 14.0% among Hispanic households compared to 2.5% among Asian households and 3.0% among White households.

While providing payment optionality for products and services, a checking account also offers safety and protection. Storing your cash at home poses several risks, whether it’s a natural disaster, robbery or fire. On the other hand, consumer bank accounts at federally insured institutions — the FDIC’s standard deposit insurance — covers up to $250,000 per person, per bank. The convenience of a checking account shows up when paying monthly bills and with a debit card, cash is conveniently withdrawn when needed. Furthermore, getting access to mainstream credit like loans or credit cards are nearly impossible or extremely expensive without a bank account.

The History of Sending Money

One may think, “it’s 2020, we have self-driving cars, how are there communities of Americans that don’t have a way to pay for the essential things in their lives”? To understand where we are now, it helps to understand some of the key developments in the history of how money and payments were handled.

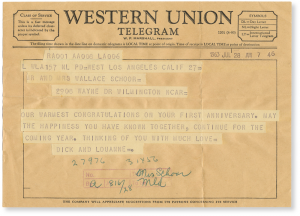

Few realize that Western Union started out as a telegraph messenger in 1851. With a network of locations across the United States, Western Union allowed people to receive information, and news over great distances. It wasn’t until 1871, however, that the company began to send money electronically. This completely changed people’s access to money in the United States, allowing individuals to quickly and securely send money across state lines and long distances. Since then, Western Union has expanded its services and network (over 500,000 agent locations in 200 countries and territories). Customers can send money domestically, pay bills, check exchange rates, track a transfer, make an international money transfer and more. These services are especially helpful for those with little or no access to traditional financial services (banks), where Western Union serves as a trusted broker.

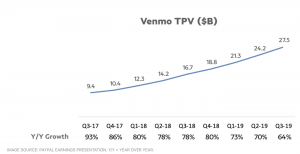

A century and change later, in 2009, former college roommates at the University of Pennsylvania, UIqram Magdon-Ismail and Andrew Kortina founded Venmo. What began as a way to help launch their friend’s frozen yogurt shop would later dramatically change the relationship people (especially millennials) have with their banks. Magdon-Ismail and Kortina focused on fixing the inadequacy of traditional point-of-sales software. They developed a product to send cash through text before pivoting to a smartphone app. The next year they raised a seed round of $1.2M before selling Venmo to Braintree, two years after that. It wasn’t until after PayPal’s acquisition of Braintree in 2015 that Venmo’s awareness began to grow. Today, over 40M people are transacting nearly $30B over Venmo each quarter.

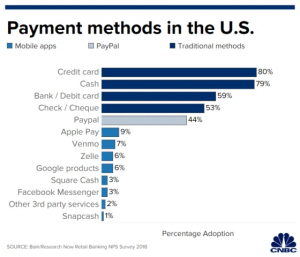

Since Venmo, a number of payment apps have sprung up. Square — a point of sale hardware and software service, favored by small retailers, launched Square Cash App. Apple’s Apple Pay Cash and now even has a credit card. While banks Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo joined forces to create Zelle which allows person-to-person (P2P), business-to-consumer (B2C), and government-to-consumer (G2C) payments. Over the past five years, payment apps have been on the rise. Since 2015, the ‘proximity mobile payment’ market (the method of payment that is initiated from a mobile phone that uses Near Field Communication (NFC) technology) has grown from just under $10 billion to almost $114 billion in 2019, and is expected to reach $190 billion by 2021. However, all these services require a user to have a bank account or debit card to take full advantage of the platform.

Cash is King — but for how long?

Credit cards were first introduced in the 1950’s and debit cards came out a couple decades later but their popularity has dramatically increased especially once the first rewards cards were introduced in 1987. Technology, of course, had a huge role in the development of cards. IBM introduced the magnetic stripe certification feature on credit cards in the 1960s. Forty years later credit card providers switched to the radio frequency identification card (RFID), allowing for faster transactions and an added layer of security. Today, cards have a range of features including biometric identification allowing you to gain access through facial, touch and/or eyeball identification.

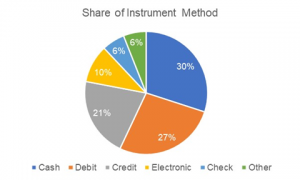

As retailers go online to meet consumer trends, payments continue to move from paper to plastic and ultimately digital. The 2018 report on the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice (DCPC) conducted by the Federal Reserve found that between 2015 and 2017, cash as a payment method decreased from 33% of volume to 30%. And while cash is the most used method of payment for purchases under $10 (55%), debit cards and credit cards were used in nearly half of all transactions. The report also highlighted the growing change in consumer preference from cash to that of credit cards, debit cards and electronic payments (payments include bank account number payments, online banking bill pay, and payment services like PayPal.)

According to the 2019 Mobile Payments Market — Growth, Trends and Forecast (2020–2025) report by Mordor Intelligence, the use of mobile payments will grow at a CAGR of 27% from 2020–2025 as vendors and retailers continue to accept payments through applications like PayPal, Samsung Pay, Apple Pay, AliPay, and WeChat Pay.

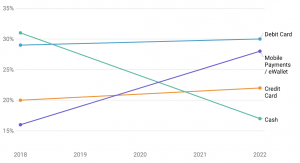

Global Share of Point of Sale Payment Methods 2018–2022

However, it’s not just consumers. Retailers have been moving away from cash for some time. Some retailers have even gone as far as dubbing themselves ‘cashless’ such as restaurants Sweetgreen and Tender Greens. By removing the cash option at the counter, retailers save time and money. Eliminating cash payments eliminates the costs associated with handling and transporting cash. Businesses no longer need to pay extra hours for employees to count and manage register balances throughout the day, enabling employees to spend more time helping customers instead. Transactions are faster and more importantly, there are fewer opportunities for theft (both inside and outside jobs).

But there are several costs associated with moving away from cash. It can take several days for the money to become available in a business’ merchant account (especially with a credit card) and there’s the dreaded credit card fees that the likes of MasterCard, Visa and American Express push onto retailers. The cost of going cashless seems worth it for retailers. The major cost, however, is paid for by consumers, in the form of financial inclusion, or lack thereof. Consumers that don’t have access to savings or checking accounts (and therefore unable to use debit cards, credit cards and mobile payment apps) are unable to fully participate in retail.

And because of these costs, restaurants like Sweetgreen and Amazon’s physical retail stores have walked back their decisions to go cashless after a backlash from un-and-underbanked consumers, and a broader push-back from cities and states against cashless stores has emerged in the last year. There finally seems to be an understanding that there is a divide between those with access to easy payment methods and those without, and that divide has real societal implications.

A New Way to Pay (and Get Paid)

Lack of payment options are just one challenge for the unbanked. Getting paid is another problem. Without a bank account, unbanked employees can’t take direct deposit, or face fees up to 15% when trying to cash a check. What these groups of people desperately need is a frictionless and free way to transfer the fruits of their labor into the goods and services they want.

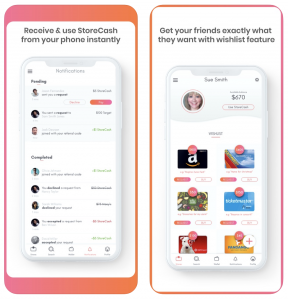

This is why we are excited to announce our investment into StoreCash, a developer of a payment application designed to manage and make payments instantly. The StoreCash app provides cash credits to over 200 retailers instantly on your phone without fees — credits that can be used as a currency for the unbanked. Similar to a credit card, StoreCash pushes the transaction fee to the retailer, but unlike a credit card or Venmo, the receiver is not required to have a bank account allowing unbanked individuals the ease and benefit of a credit card or mobile payment solution without the strict requirements.

MaC Venture Capital led this seed round into StoreCash, with Western Union, Mucker Capital, Correlation Ventures, and Techstars also participating. Marlon Nichols led this deal for MaC VC.

Having gone through the Western Union Techstars branded accelerator in Denver in 2019, StoreCash has built a strong relationship with the company and the two are working closely together to build solutions for the 40M people in the United States who currently use Western Union to send and receive payments.

StoreCash was founded by Daricus Releford whose story is an extraordinary one. A serial entrepreneur who started his first business with his twin brother at age 12, Daricus rolled one successful venture into the next, ultimately starting a local berry business called Twigedies Berries that landed Daricus and his brother an article in Kiplinger Magazine and an appearance on the Steve Harvey show. Seeking funding and an expansion of his berry business, Daricus traveled west from Pennsylvania to Silicon Valley where he landed something just as valuable — jobs working for Apple, then Facebook and finally Google where he worked as a strategy and operations coordinator. The berry business grew into a larger gifting company that ultimately gave birth to the idea of StoreCash.

Daricus recruited his Co-Founder and CTO Phani Mullapudi from Adobe where Phani was working as a senior computer scientist and software engineering lead. Sheetal Ravi rounds out the founding team as Head of Design.

The StoreCash Experience

The StoreCash platform is relatively straightforward: users can transfer credits between one another, and those credits can then be used to make purchases at one of the StoreCash retail partners or they can be cashed out as US dollars via the Western Union partnership. The goal of the platform is to enable Venmo-like functionality for those who are otherwise unable to utilize mobile payment platforms due to a lack of banking status.

Employers ranging from Google down to a homeowner paying for a lawn-mowing job can pay (or bonus) their workers easily through the app without the need of a bank account. Those workers can then redeem that payment through the app for thousands of items via the simplicity of a digital gift card. Retailers are happy to pay a transaction fee to StoreCash because for them, this is low-cost customer acquisition. Western Union is happy to provide cash-out services because StoreCash expands their suite of services and overall customer base.

StoreCash measures success through the number of transactions flowing through its platform. The company is working to partner with more retailers to ensure that its customers have the ease of payment wherever they choose to shop.

Since launch, StoreCash has gained new partnerships such as DoorDash, UberEats, and GrubHub gift cards. The company is continuously improving its app to meet user needs: due to a high demand in sending its in-app currency to many users simultaneously, StoreCash created an automated tool for enterprise companies to make bulk StoreCash transfers for customer loyalty and employee rewards programs.

Other digital payment platforms like Paypal, Venmo, and Zelle can’t address this need. All require customers to link to their bank accounts. This is not possible for the unbanked and difficult for the underbanked. Furthermore, those payment solutions are not accepted at physical retail locations. With StoreCash, a user can go shop at a store and use the app at the checkout counter as they would a physical or digital gift card.

At MaC we like to focus on companies that are gap closing vs gap widening. And as the wealth gap in the US continues to widen, we need companies like StoreCash to solve real problems for millions of Americans who historically have not been the focus of big Silicon Valley startups. By providing a platform that makes it easier for the unbanked and underbanked to participate in the economy, StoreCash is doing its part to help narrow the divide.

About MaC Venture Capital

MaC Venture Capital is an early-stage venture capital firm focused on finding ideas, technology, and products that can become infectious. We invest in technology companies that benefit from shifts in cultural trends and behaviors in an increasingly diverse global marketplace.

MaC Venture Capital is the result of the merger between successful Los Angeles and Bay Area-based Seed funds, Cross Culture Ventures, and M Ventures.