How LA-Based Ryff Uses Gaming Technology for Surgical Product Placement

f you watched this year’s NCAA basketball tournament, you may have unknowingly witnessed an early milestone from a company aiming to upend video advertising.

Ryff, a stealthy L.A.-based startup founded in 2018, helped Coca-Cola insert images of Coke bottles and banners into classic footage from past tournaments, like UCLA’s 2006 finals run and North Carolina State’s improbable championship in 1983.

Ryff’s ambitions are much grander than clever, nostalgic ads: chief executive and co-founder Roy Taylor wants to introduce on-demand digitized product placement across the entire entertainment industry.

Traditional product placement often requires complex upfront negotiations between brands and content producers, or using post-production techniques that can be costly and clunky. Ryff uses technology common in video games, where on-screen items can be swapped in and out at the push of a button, to quickly insert branded images into completed scenes. This approach distinguishes the L.A.-based startup, but could raise questions from creators who never set out to be brand ambassadors and viewers who will be unwittingly exposed to ads.

Taylor himself is reluctant to seek out too much publicity for fear of a backlash.

“We’re in a slightly unusual position because we want all the publicity we can get, but only B2B,” he said, meaning he wants brands and content-owners to hear about Ryff, but not necessarily viewers.

“We believe the general public, if they have a preference, veer towards being less comfortable with digital anything right now,” Taylor said. He is adamant, however, that Ryff does not create “deep fakes.”

“We do not change an original truth; I think that’s wrong,” he said. “I would never allow our technology to be used in a way which is nefarious.”

In addition to its Coke campaign, Ryff has done a test campaign with Diageo, for which it inserted Baileys bottles into three Lifetime movies, as well as a handful of other brands and firms including Intel, Perfectamundo tequila and Dutch production company Endemol Shine. The startup has raised $8.6 million.

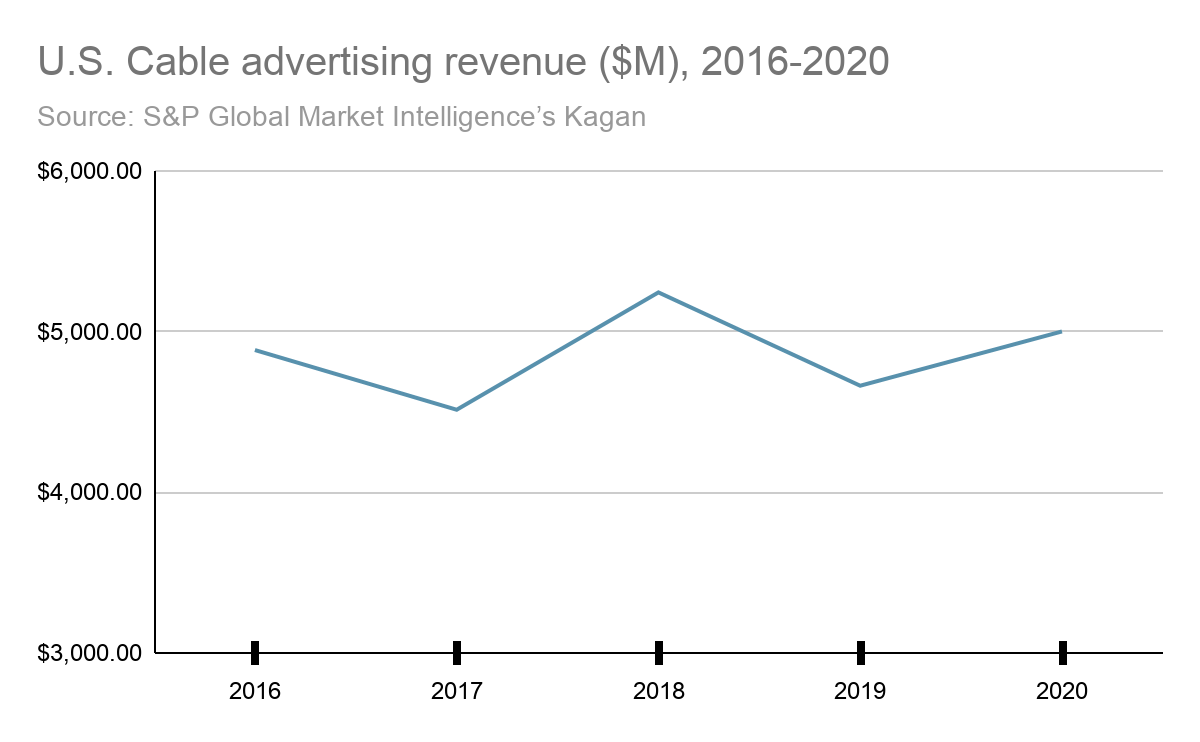

As linear TV viewership has declined, advertising dollars on the medium have stagnated. They have “proven relatively resilient, despite core cutting,” said media analyst Tony Lenoir of Kagan, because advertisers like being able to reach the customers that have stuck with cable, who tend to be relatively wealthy.

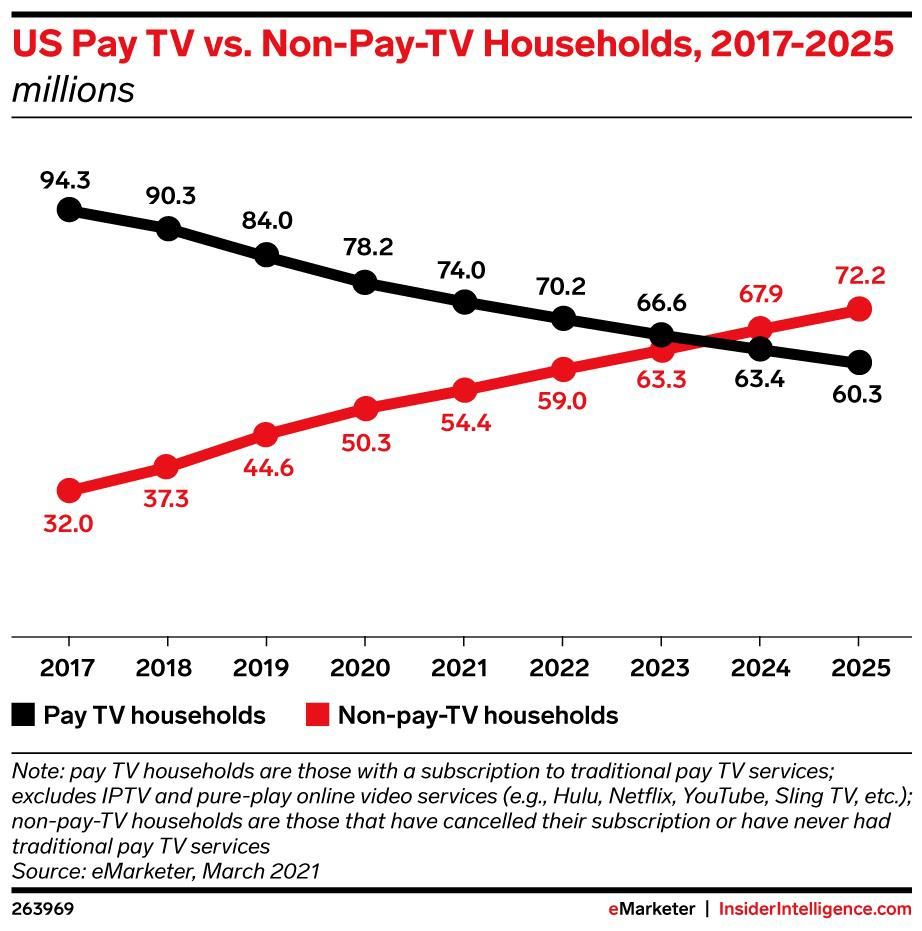

But TV ads have been in steady decline as a share of overall advertising spend. From 2015 to 2020 the share of TV ad-spend in the U.S. fell from 42% to 33%, with a further decline to 20% expected by 2025, according to MoffettNathanson, an independent research company focused on media and communications. Online advertising, which includes streaming, has picked up the slack, growing from a 27% share in 2015 to 52% in 2020, with an expected rise to 73% by 2025. Relatedly, eMarketer predicts that by 2024, there will be more households without a traditional pay-TV service than with it.

Taylor’s investors think he and his 30-person team, split between L.A. and Cambridge in his native U.K., are well positioned to ride these trends.

“I think streaming platforms, because there’s so many of them now, will need to identify new ways of generating revenue outside of growing the subscriber base,” said Marlon Nichols, whose MaC Ventures participated in Ryff’s $5 million fundraise in 2019, its most recent.

Ryff’s biggest competitor is London-based Mirriad, which Taylor says uses technology that is less scalable. That could change, however.

“There is no such thing today as a product which cannot be replicated,” he said.

Like any multi-sided platform — think Uber, Airbnb, etc. — Ryff will need to onboard users on both the supply and demand sides of the ad market. In other words, to achieve its ambitions of ushering in a new paradigm of advertising, Taylor needs to lure in more brands on the one side, and streaming platforms, studios and UGC video services on the other.

Ryff has done a test campaign with Diageo, for which it inserted Baileys bottles into three Lifetime movies.

How Ryff Works

To demonstrate his technology, Taylor pulls up a scene from a film he cannot disclose, of two men sitting on stools outside a restaurant, at a small table holding two empty glasses.

Using a combination of computer visioning and artificial intelligence, Ryff’s “Placer” technology has scanned the entire film to identify opportunities like this for product placement. The tool, Taylor said, is trained to recommend product types that fit scenes contextually, culturally and creatively.

In the restaurant scene, that means the technology should know not only that a beverage bottle could fit, but also that it must be a brand that could be found in whichever country the scene is taking place. The product also must fit with the story’s narrative; if both characters are teetotalers, the technology could suggest a soda brand, but not a beer.

“I took the notion that you could treat a frame of film or TV as a backdrop, like in a traditional theater,” Taylor said. “You could take a 3D model and render it — that is, apply light and shade to it — and make it look as though it appeared in the backdrop; you could get them to match.”

Ryff’s automated suggestions are uploaded into a searchable database that brands can screen for myriad factors, including the time of day the scene takes place, specific actors in it and whether it contains certain activities like sports.

Taylor drew on his background at NVIDIA to create Ryff. The Silicon Valley company makes chips and graphic processing units. In the 1990s, he helped launch its European offices.

Read the rest of this piece on Dot.LA