Does a Toddler Need an NFT?

More News

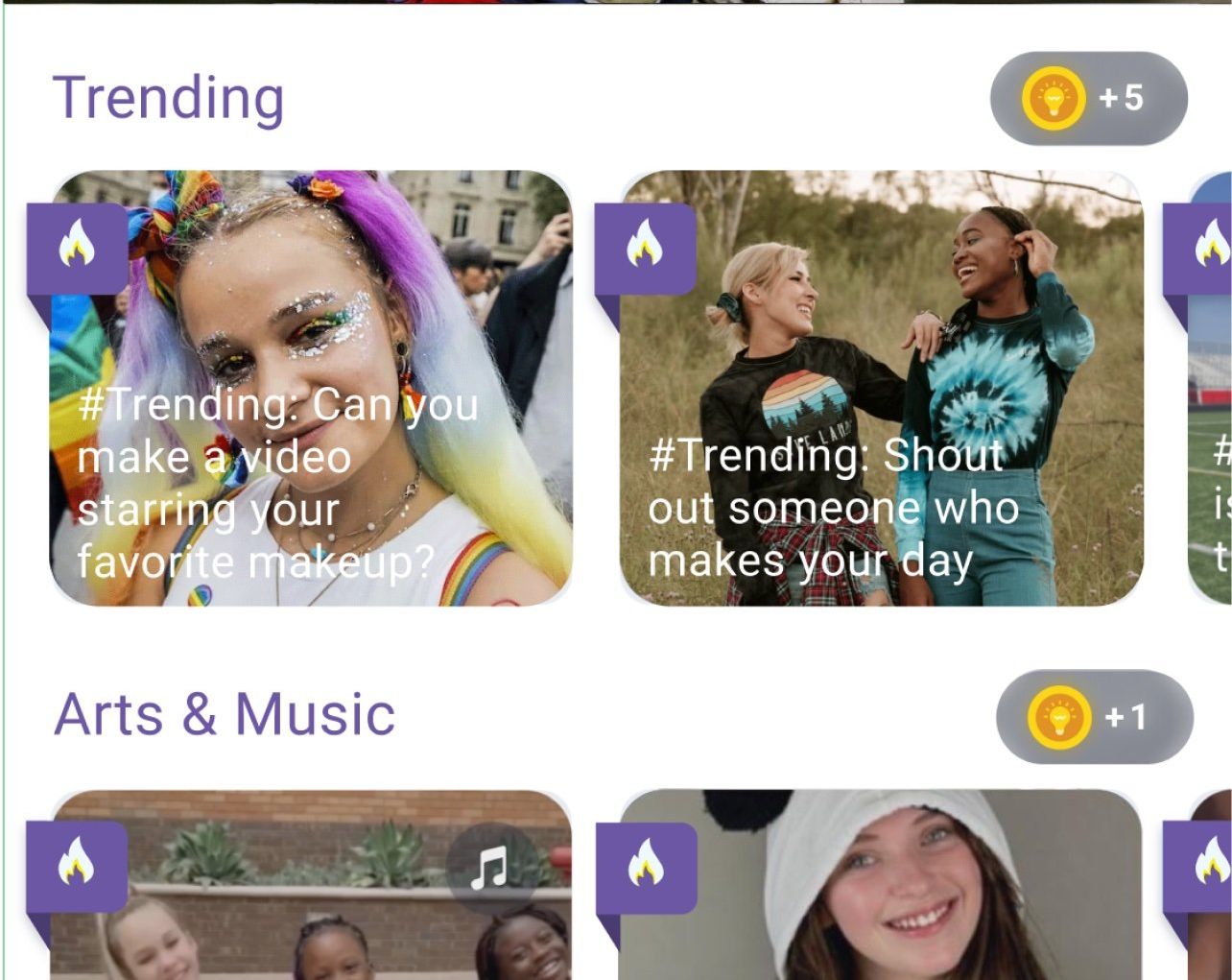

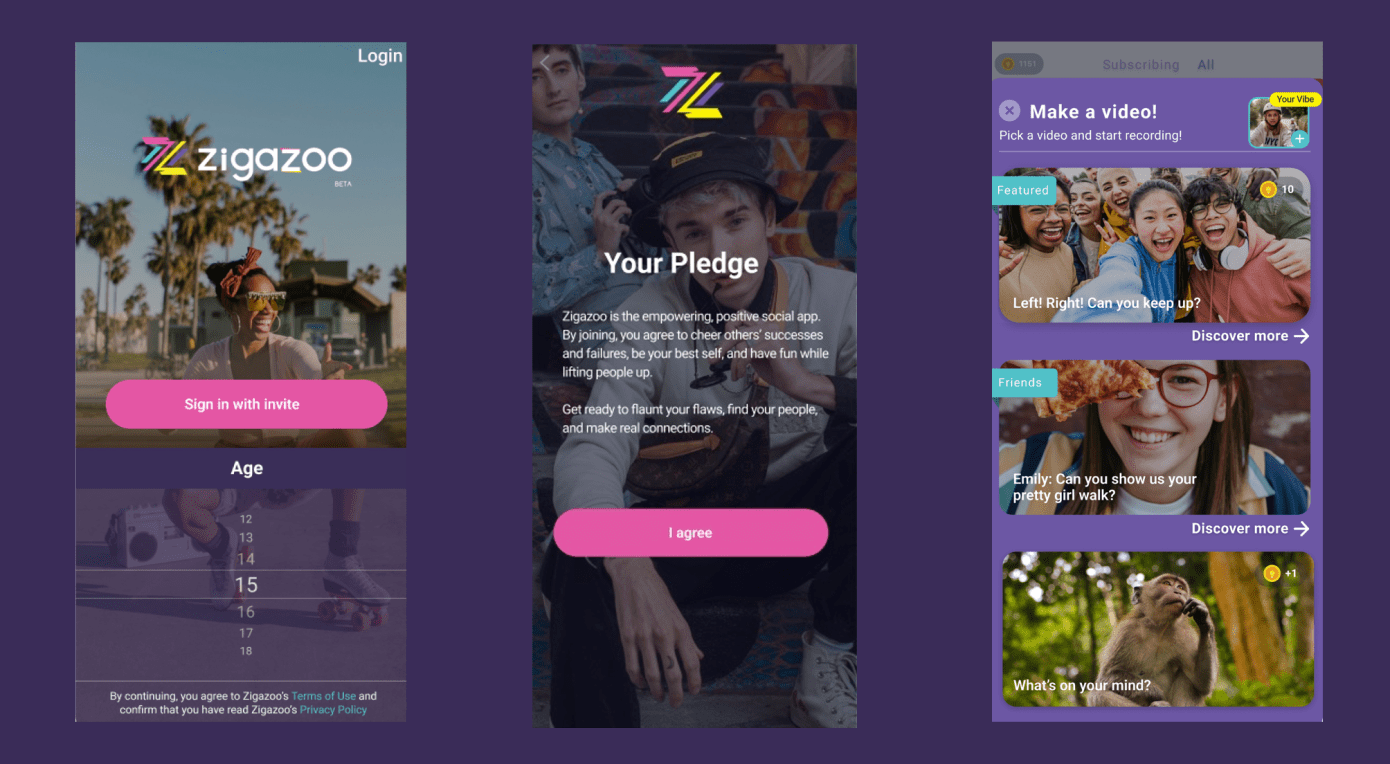

Zigazoo CoverageWith a TikTok Ban on the Horizon, Zigazoo Is Working To Attract Teens.

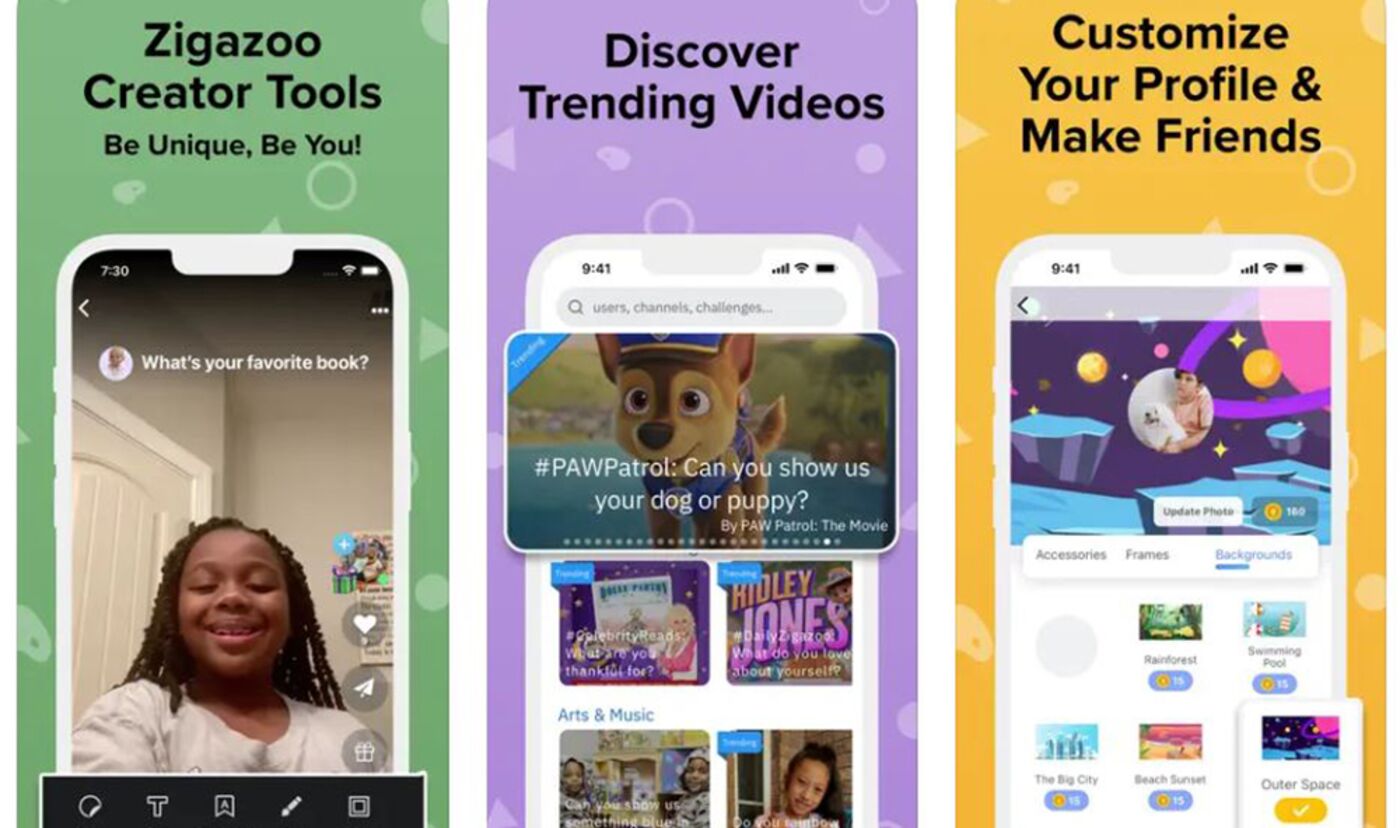

Read More >>Kid-focused short video app Zigazoo launches a TikTok competitor for Gen Z.

Read More >>WWE to partner with Zigazoo, the No. 1 Social Media App for Kids, in the weeks leading to WrestleMania 39!

Read More >>Moonbug Entertainment And Kids Social Platform Zigazoo Launch ‘Blippi’ NFT Collection

Read More >>NBA Invests in Celebrity-Backed Kids’ Social Network Zigazoo

Read More >>Crypto universe: How a 13-year-old makes millions selling NFT art

Read More >>Scoop: Zigazoo debuts kid-safe NFTs from Moonbug and Serena Williams

Read More >>Social Media for Kids: Zigazoo is The Next Big Thing

Read More >>Zigazoo is, ‘a controlled environment where kids are creating… as opposed to passively consuming content’: Zigazoo Co-Founders

Read More >>Tik Tok for Tykes: The Social Streaming Company Driving The Next Evolution in Kids’ Media

Read More >>A social media app that’s truly safe for kids? Celebrities bet on Zigazoo

Read More >>

View More Portfolio Company News

Select Another Portfolio Company